aech - tidal fish traps of yap

By Daniella LoScerbo and Heather Earle

Ancestral Connections & Geographic Extent Temporal Extent Biophysical Manipulations Target Species Ceremony & Stewardship Current Status

Aech, Yap Island - Photo by Bill Jeffery

Ancestral Connections & Geographic Extent

The Yapese people constructed and maintained hundreds of tidal traps and weirs made from stone and wood on the islands of Yap. Yap is situated within the Federated States of Micronesia (also referred to as Remote Oceania) and is comprised of three high volcanic islands, Maap, Rumung, and Marbaa, and a number of outer islands and atolls (Jeffery and PItmag 2010). An extensive survey of fish traps on Yap documented over 800 on mainland Yap (Falanruw and Falanruw 2003), although more have been found since 1996 when the study was conducted (Jeffery and Pitmag 2010). Similar traps to the those built by the Yapese were also found on other Micronesian islands such as Palau, Lukunor and Nanoluk, Ifaluk, Ponapae, the Gilberts, the Marianas, and Kapingamarangi (Kikiloi, 2003).

Temporal Extent

The fish traps and weirs of Yap have not been dated and it is not known exactly when the first ones were built (Jeffery and Pitmag 2010). Yapese people talk about the first seven aech being constructed by spirits, more than a thousand years ago, with all other aech descending from these original seven types (Jeffery 2013; Jeffery and Sellmann 2020).

Biophysical Manipulations

Stone tidal fish traps on Yap take on a variety of different forms, from small bamboo weirs to the extensive and well-known arrow-shaped stone traps called aech (Jeffery and Pitmag, 2010). Of all the different configurations, arrow traps are the most durable and extensive fishing structure seen today on Yap, making up about 67% of the more than 800 traps documented (Hunter-Andreson 1981; Jeffery and Pitmag 2010).

Aech were built near the shore, with the tip of the arrow pointing seaward in the direction of the outgoing tide and the shaft of the arrow beginning near the shore (Jeffery and Pitmag 2010). The arrow shafts, varying in length from 20 to 200 meters, serve as a barrier to fish swimming along the coastline, guiding them along the shaft into the head of the arrow where they are trapped when the tide recedes (Jeffery and Pitmag 2010; Jeffery 2013). Fish are guided into a single large chamber within one side of the arrow head, although in some cases there were additional smaller chambers into which only smaller fish could enter, preventing larger fish from eating them (Jeffery 2013).

The height of the walls would vary within an aech and was determined by the depth of the water, the local sea conditions, and the movement of fish (Jeffery 2013). The walls varied in height, depending on the location, but were generally below the high tide line so that fish could escape at the highest tides (Jeffery and Pitmag 2010). Once inside the chambers, the fish were prevented from exiting either by bamboo weirs attached to the gates or by minor inflowing currents created by the placement of rocks around the gates. Fish were removed from the stone traps using bamboo traps (yanup), spears, or small butterfly nets (ke’f) (Jeffery 2013). When not in use, gaps were left in the shaft wall which allowed the fish to swim through the aech while also reducing the build up of sand in the chambers (Jeffery 2013).

The configuration and distribution of aech suggest that the Yapese people were highly knowledgeable of fish behaviour and movement. Many traps were constructed around deep holes in the lagoon floor, with the tip pointing toward the hole’s center, targeting fish retreating to these depressions with the ebbing tide (Falanruw et al. 2003). Cited in Jeffery (2013) Falanruw comments that “it is though the whole lagoon were a fishpond, with aech serving as fish concentrating gates located at strategic points, thus providing an efficient way to harvest fish. Today we could learn a good deal about patterns of fish movement and routes of spawning aggregations by analyzing the configuration of each aech”.

Aech chamber - Photo by Bill Jeffery

Aech wall - Photo by Bill Jeffery

Target Species

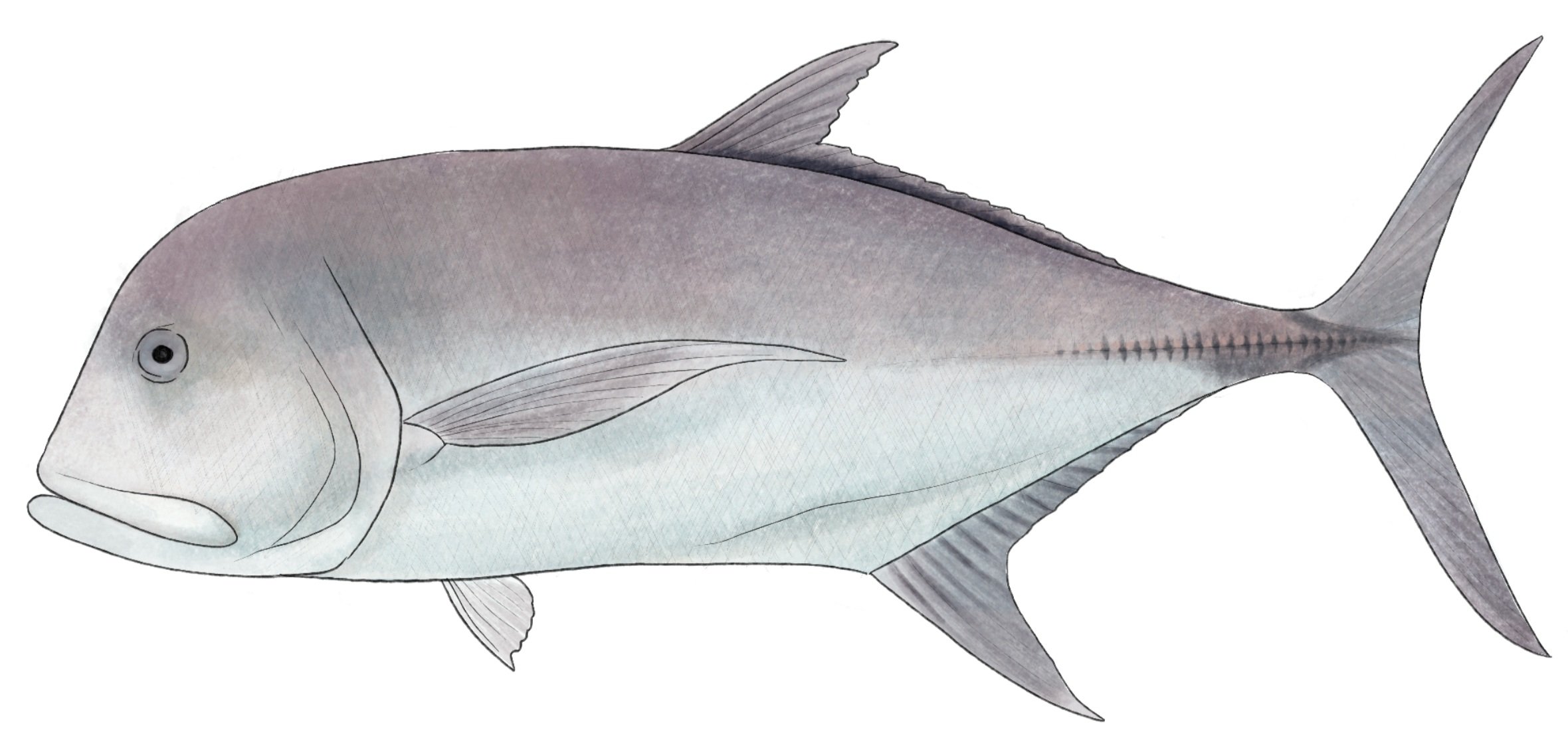

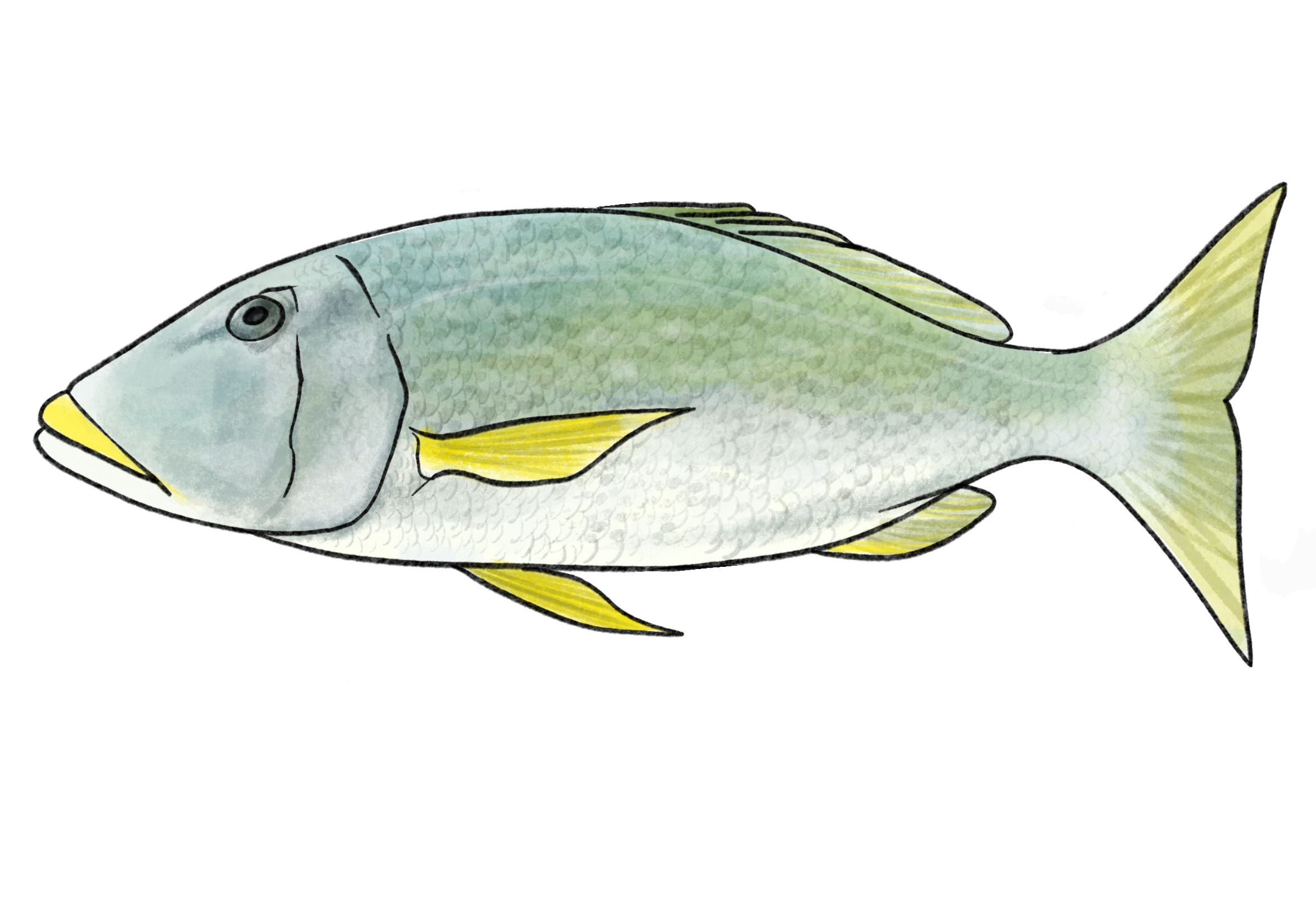

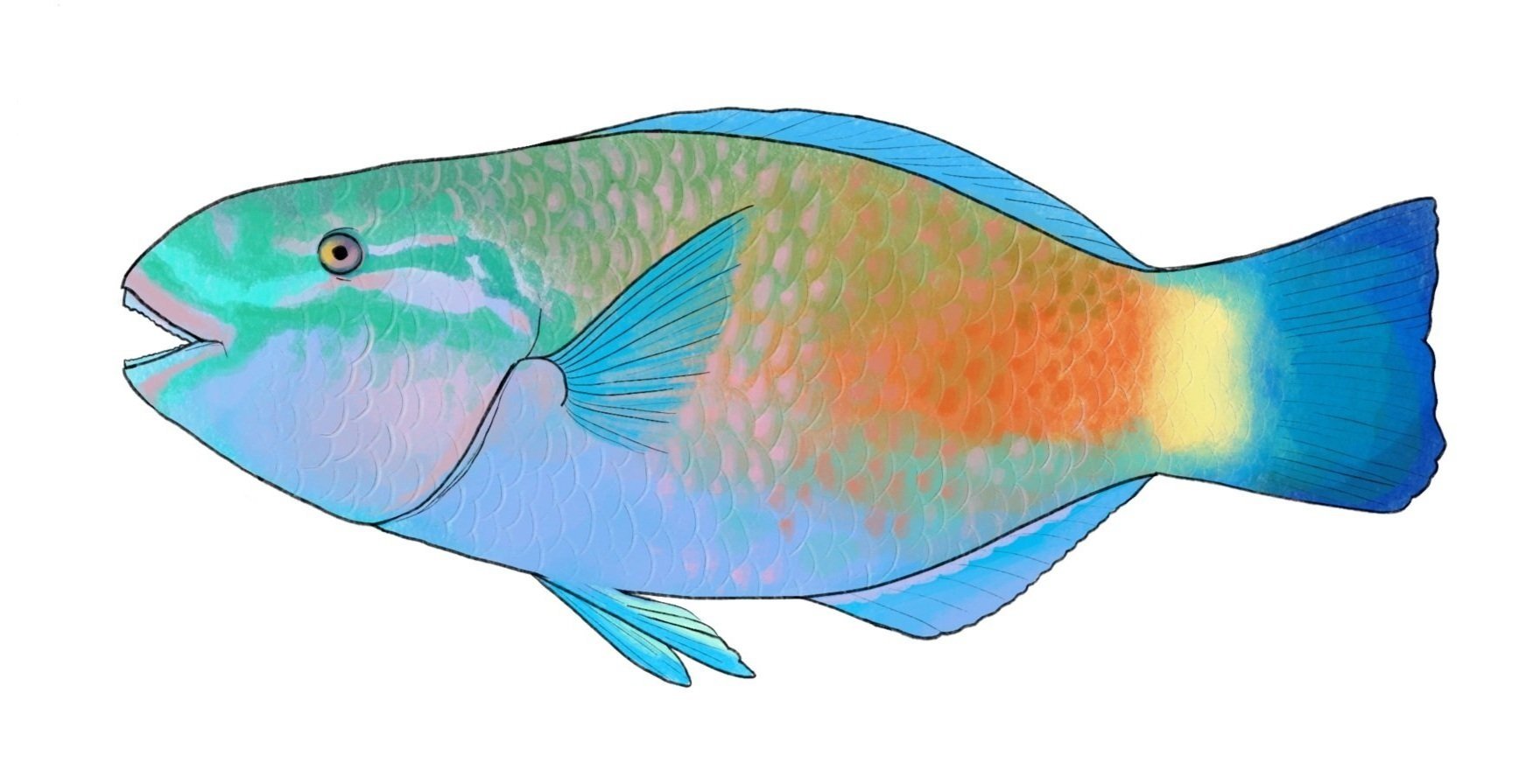

The types of fish caught were dependent on the habitat in which an aech was situated (Jeffery and Pitmag 2010). Those on seagrass beds predominantly caught rabbitfish (Siganus sp.), goatfish (species unknown), yellow-lipped emperor fish (Lethrinus xanthochilus), long-nosed emperor fish (Lethrinus miniatus) and needlefish (species unknown); while those built on reefs caught Green humphead parrotfish (Bolbometopon muricatum), bullethead parrotfish (Chlorurus sordidus) surgeonfish (species unknown), triggerfish (species unknown), giant trevally (Caranx ignobilis), barracuda (Sphyraena sp.), shark (species unknown), grouper (species unknown), stingray (species unknown), and sea turtle (species unknown) (Jeffery and Pitmag 2010).

Ceremony & Stewardship

Yapese society is highly structured; within villages, there are both high and low caste families and the latter are not permitted to own land (Jeffery 2013). Sea-plots (submerged land) are owned by high class family estates with lower caste villagers occasionally given access. Yapese women were typically prohibited from fishing and therefore harvesting from aech was conducted by men, as men’s work was described as being in the sea and women’s work on the land (Jeffery and Pitmag 2010). Fishing was often carried out by multiple families such that the catch could be shared and villages supported one another during years of both plenty and famine (Jeffery 2013).

Building aech required a considerable amount of manual labor and materials. Arrow traps required continual maintenance to keep the walls high as tidal currents and storms tended to impact their integrity. The yield from an arrow trap was significant with the catch from one side well exceeding the needs of a single family (Hunter-Anderson 1981). Fish were caught at specified times, for only a few days, then stones in the aech were removed to let the fish come and go such that they would “feel at home” (James Lukan, cited in Jeffery and Sellmann 2020). This increased the sustainability of the practice as there was a good possibility that not every fish that entered the trap would be caught (Jeffery 2013).

Current Status

Although there are more than 800 aech documented on Yap, relatively few are still in use today (Falanruw et al. 2003) and many have fallen into disrepair (Jeffery and Pitmag 2010). There are several factors that have contributed to the decline of aech, beginning with the colonization of Micronesia, including Yap, that began in 1521 and brought a string of Spanish, French, Russian, German, English, Japanese, and American explorers, colonialists, missionaries, and traders to the region (Jeffery et al. 2021). Colonization greatly impacted the Indigenous people of Yap, many of whom lost their lives to diseases, drastically reducing the populations of the islands from approximately 40,000 pre-contact to 2,500 immediately after World War II (Jeffery 2013). These population declines likely diminished the need for large catches, likely to the point where the benefits of stone fish traps no longer justified the labour costs associated with maintaining them (Hunter-Anderson 1981).

The need for stone fish traps further diminished with the incorporation of modern fishing gear into the Yapese economy following the second world war, which was comparatively cheap (Falanruw et al. 2003). As well, many of the traps were dismantled during Spanish occupation in the late 19th century (Jeffery and Pitmag 2010) and Japanese occupation from 1914 – 1945 (Hunter-Anderson 1981).

Today, Yap is one of the four states of the independent nation of the Federated States of Micronesia (Jeffery 2013) and in recent years, there has been significant effort and interest towards restoring aech and the cultural practices that go hand in hand with them (Jeffery and Pitmag 2010; Jeffery 2013). In 2008, the Yap State Historic Preservation Office contracted Bill Jeffery to survey the weirs of Yap in order to assist in prioritizing restoration work (Jeffery and Pitmag 2010). The Yapese community formulated the project and saw it as something that young men in the community could get involved with to increase engagement in an important part of their culture while fostering the community spirit needed to revitalize the aech of Yap. Following typhoon Sudal in 2004 which damaged a number of aech, owners were provided with funds to restore their stone weirs, with many restoration efforts being successful, and many more underway (Jeffery and Pitmag 2010).

Aech on Yap Island - Photo by Bill Jeffery

References

Falanruw, M.C. and L. Falanruw. 2003. Stone fish weirs of Yap. SPC Traditional Marine Resource Management and Knowledge Information Bulletin - Special Edition, 16. Department of Zoology, University of Hawaii.

Hunter-Anderson, R. L. 1984. Yapese stone fish traps. Asian Perspectives 24:81–90.

Jeffery, B. and W. Pitmag, W. 2010. The aech of Yap: a survey of sites and their histories. Yap State Historic Preservation Office. Yap, Federated States of Micronesia.

Jeffery, B. 2013. Reviving community spirit: furthering the sustainable, historical and economic role of fish weirs and traps. Journal of Maritime Archaeology 8:29–57.

Jeffery, B. and J.D. Sellmann. 2020. Yapese environmental philosophy and food sustainability. Paper presented at the Asia Pacific Society for Agricultural and Food Ethics Conference, December 2020.

Kikiloi, K. 2003. A new synthesis in oceanic domestication: the symbiotic development of loko iʻa aquaculture in pre-contact Oceania. SPC Traditional Marine Resource Management and Knowledge Information Bulletin no. 15.