intertidal salmon fish traps - southeast alaska

By Steve J. Langdon

Ancestral Connections & Geographic Extent Temporal Extent Biophysical Manipulations Target Species Ceremony & Stewardship Current Status

Ancestral Connections & Geographic Extent

It is not known who the innovators of intertidal fish traps were in southeast Alaska. They may have been invented by the Tlingit or possibly Eyak or another unknown early population. A case can be made for Tlingit presence dating to the earliest appearance of human populations but a much stronger case can be made for their presence by 6000 BP through linguistic and artifactual (spruce root basketry) evidence. Archeological evidence of human presence in proximity to salmon spawning rivers is shown by the Thorne River site dated to 8750bp – no fish traps or evidence of salmon use has been obtained from that site.

Sea level changes since the period of earliest occupation of southeast Alaska (Ground Hog Bay) have drastically altered the land-sea interface thus moving the intertidal zone significantly over this period (Carlson and Baichtal 2015, Putnam and Greiser 1993). Most archaeological accounts suggest a falling sea level from considerably higher level stabilizing near current levels by 5-6000bp (Moss et al 2016).

Brief mention is made of Tlingit intertidal salmon fish traps in de Laguna (1960) and Emmons (1990). Fish trap ownership, tenure and management authority was vested in a clan or house leader who took responsibility for sustaining the return of salmon to the stream under his or her jurisdiction (Langdon 2006a).

The Tlingit have several oral traditions about learning to create and use intertidal fish traps to capture salmon. The Tek’weidi are a clan of the Wolf/Eagle moiety whose primary crest is the brown or grizzly bear. In their origin account, ancestors observed the grizzly bear obtaining salmon from natural pools in which salmon had been caught as the tide receded. They then began building their own traps. In another unattributed account, Tlingit ancestors observed Raven (the mythic transformer/trickster), building a trap with small stones. Both of these accounts are in the Tlingit tradition of learning from or being taught by other co-equal members of the existential community with whom they interact.

Today, virtually all intertidal lands below mean high tide in southeast Alaska are owned by the State of Alaska even those abutting the upland governed by the US Forest Service and National Park Service. There is no known current use of sites with intertidal fish traps. The last reported occurrences were in the 1950s and 1960s.

Current archaeological evidence indicates that the use of intertidal stone structures was quite common in southern southeast Alaska and particularly on the west coast of Prince of Wales Island where they are found on nearly every stream (Langdon 2006a, 2007; Smith 2011). However, the abundance and density in that area may be the result of large-scale intertidal research done there in the 1980s and 1990s (Langdon et al 1986, Langdon 2006b, 2007). North of Frederick Sound, in northern southeast Alaska, many fewer intertidal salmon fish traps have been reported (Smith 2011).

Major factors to consider in understanding the geographic extent of intertidal salmon fish traps in southeast are tectonic uplift (changing sea levels) that may be highly localized in their impacts (Putnam 1996) and lack of systematic regional surveys. As Fig. 1 indicates, the highest density of intertidal fish trap sites is in southern southeast Alaska have been identified where systematic surveys of the intertidal zone have been conducted (Langdon et al 1986, Langdon 2006, 2007).

Intertidal weirs and fish traps reported in southeast Alaska (Smith 2011)

Temporal Extent

Intertidal fish traps and weirs can be constructed out of wood or stone. In a few cases both materials are combined into compound structures (Langdon 2006a). Within the current tidal range, the oldest radiocarbon dated fish trap is 5500 cal 14C years bp (Smith 2012). As of 2012, 111 sites in southeast Alaska had been dated (Smith 2011). See Smith (2011) for compilation of radiocarbon dates.

However, intertidal salmon traps constructed out of stone are notoriously difficult to directly date. At the outset of research in the mid-1980s, we hypothesized that deposits behind intertidal stone traps might hold datable materials. At the site known as Little Shakan, we undertook excavation in deposited sands behind the stone weir intersecting the stream at mid-tide level (Figs. 2, 3 and 4). Voila! We uncovered a buried wood stake that was subsequently radiocarbon dated to 1030+/-60bp (uncorrected – Beta 20077).

Chris Wooley by Little Shakan weir - Photo by Steve Langdon

Wood stake buried in Little Shakan weir - Photo by Steve Langdon

Excavated portions of sediments deposited behind Little Shakan weir - Photo by Steve Langdon

Form and Context

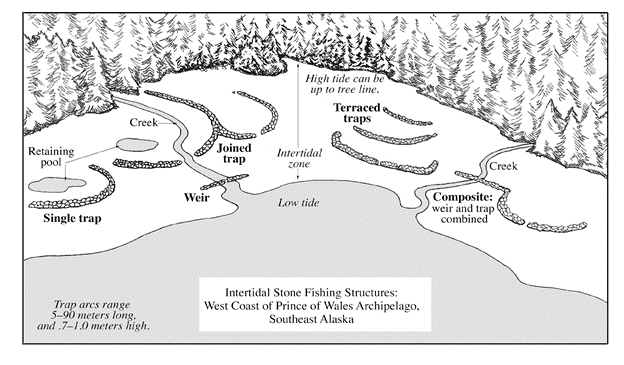

Intertidal fish traps were constructed in a variety of shapes and forms. In the Prince of Wales Archipelago, common forms included semi-circular arcs (single trap), bi-lobed semi-circular arcs (joined traps), linear weirs, and composite forms joining weirs and traps. Fig. 4 shows the variety of stone forms that appear in that area. Smith (2011) displays a variety of other forms that appear elsewhere in southeast Alaska. In a number of cases, wood and stone materials were combined depending largely on the intertidal composition and nearby stone materials.

Types of Intertidal Stone Fish Traps – West Coast Prince of Wales Archipelago (Langdon 2006b)

Contexts influence the positioning, shape and materials used in the traps. Preferred sites are generally flat areas with no outcroppings that have relatively low slope. The low slope provides a moderate rate of tidal retreat that nevertheless dries up rapidly thus hastening the capture of the salmon. If there is one basic unit of fish trap, it will be positioned in the current middle area of the intertidal zone. This is done to be operational on the larger and smaller high tidal stages that occur daily in this region.

One variety is a positioning immediately outside of the stream channel. The semi-circular arc opens to the upland side. In some cases, the arc intersects and crosses the stream channel. Bi-lobed or joined traps can be positioned in either fashion. Linear weirs are found only on small streams and again are placed in the mid-tidal range area (see Fig. 2).

One of the interesting discoveries was that intertidal fish traps could be positioned at some distance from the mouth of salmon spawning streams. They are located in certain places in order to intercept larger schools of salmon that are migrating to a number of streams but travel in large schools on their migratory path from the ocean to the spawning beds. Salmon follow the shorelines and use headlands to orient on their homeward journeys.

An excellent example of an intercept location for intertidal traps is Fern Point located on the eastern shore of San Fernando Island, just west of Klawock. The Fern Point complex is distinctive in consisting of a number of intertidal traps occurring at four different levels, rather than one, in the intertidal range. This positioning results both in multiple opportunities for harvest while at the same time ensuring that at least one of the traps will be operational at all stages of high tide as their range fluctuates through the monthly cycle (Langdon 1986). Terraced and intercept traps have been identified elsewhere on the west coast of Prince of Wales Island area. Click here to learn more about the fish traps at Fern Point.

Biophysical Manipulations

There are a variety of forms, materials and biophysical interventions characteristic of intertidal fish traps in southeast Alaska. On the mainland of Alaska and on Prince of Wales Island proper where the estuaries are composed primarily of sands and muds, wood stakes were constructed from nearby hemlock and spruce trees. Invariably the stakes found buried beneath the intertidal surface when extracted have been carved into points of various kinds. The beaches of the islands of the archipelago to the west are rocky providing materials for construction. Local stones are stacked or placed on top of each other side by side to form the wall that may be part of a weir guiding salmon in a direction or a trap designed to capture salmon.

In regards to biophysical manipulation, the positioning and scale of the weirs and/or traps can result in a variety of changes to the intertidal geomorphology. This can range from minor and limited in impact for small technologies (as in the case of the intertidal weir pictured above) to major and significant impacts from larger scale and crucially positioned technologies (see example below). The V-shaped traps found in the upper estuary of the Klawock River had a significant impact on the estuarine characteristics of the intertidal zone overtime as well as on the estuarine channel of the river. The trap pictured in Fig. 6 is dated to 875bp. The V-shaped traps created sediment capture zones that over time resulted in the creation of V-pointed grassy islands and diverted the main flow of the Klawock River estuarine channel to the south (see Fig. 3). Video 2 below provides images and a discussion of the technology.

In other locations, intertidal fish traps have also resulted in geomorphological changes to the underlying substrate when associated with streams. These are generally diversions or displacements of the primary stream resulting from sediment deposition. Click here to learn more about the types of traps and their associated features in the estuary of the Klawock River.

V-shaped trap constructed of wood stakes and stone braces in the Klawock River estuary - Photo by Steve Langdon

Islands in Klawock River estuary created by sediment deposition behind the V-traps. The red Vs indicate the locations of earlier traps - Photo by Steve Langdon.

Critical Innovation: Tidal pulse fishing

Tuk’ak’ah (Little Salt Lake) is a well-protected small embayment on the coast of Prince of Wales Island about two miles north of Klawock. Two streams drain into the bay both supporting chum (Onchorynchus keta), silver (Onchorynchus kisutch) and pink (Onchorynchus gorbuscha) salmon. Research on intertidal fish traps in Little Salt Lake began in 1986. After discovering that the intertidal zone contained an enormous number and array of wood stakes (and a few stone braces), a project to map and date the various features was undertaken. The extraordinary number of wood stakes and features required several years of research documentation. Fig. 8 shows the array of features discovered and documented. Fuller discussion of the analysis of the patterning, sequence and dates of the features identified can be found in Langdon (2007).

In Little Salt Lake, radiocarbon dating of the features showed that there was a shift in the harvesting strategy that occurred between approximately 1500bp and 1000bp. In the earlier period, wood stake weir and trap features were constructed to capture salmon on the incoming tide. The form outlined in red in Fig. 8 displays this strategy with a weir funneling salmon up to holding and trap areas in the upper tidal zone. A new harvesting strategy appeared around 1,000bp, in which technologies were designed to focus harvesting on the ebb tide (Langdon 2007). The chevrons and arcs located in area Lower C in Figure 8 display this strategy.

This new strategy, termed “tidal pulse fishing” (Langdon 2006b) is found throughout the outer islands and would appear to date the expansion of the Tlingit into these areas farther from the larger streams found on Prince of Wales Island.

Weir and trap features at Little Salt Lake, Prince of Wales Island. Weirs demonstrating the “tidal pulse fishing” strategy can be seen in the area labelled Lower C (Langdon 2007).

Description of the traps provided by Christine Edenso, a Tlingit-Haida woman who observed their use (Pulou 1983:36):

I’ve observed in my younger days that … Tlingits used to trap fish at the mouth of the streams. If you go around today by the mouths of the old creek flats, you will see these rocks still piled up as they did in the old days. You will be able to see the outline of where they laid a bunch of rocks to form a wall. In that way, when the tide went out, the fish were trapped behind them and they were easier to catch then. They used to catch all the fish they needed as time went on. Some of the creeks were readily adaptable to this kind of fishing, and that was why they caught their fish by this method. The fish would go up to the mouth of the creeks at high tide. They would get behind the wall and would be trapped then the people would gaff them and pull up all the fish they needed right there. That was how they used to catch their fish. When you go along the beach at low tides, you can still see these places where they made these rock walls and traps and they are quite visible. They are the works of the people a long time ago … You can see these rock enclosures all over Southeastern Alaska on the west coast, in the tidal flats … and at any place where there was a good number of people … They used the network of fish traps to corral the fish momentarily while the tide was going out. They used to gather their fish in that way.

Target Species

Intertidal weirs and traps that have been investigated are primarily in proximity to salmon streams but are also occasionally positioned at intercept locations such as headlands (see video 2). In the Prince of Wales Archipelago, they are designed primarily for the capture of chum (Oncorhynchus keta), silver (O. kisutch), sockeye (O. nerka) and pink (O. gorbuscha) salmon. They may also have been used in a few locations to capture Pacific herring although there is no direct evidence of their use for that purpose.

Ceremony & Stewardship

In Tlingit society, clans owned territories and resources (Langdon 2006b, 2007, 2020). Jurisdiction over a stream, including the types of technologies used to capture salmon, the onset and timing of harvest, harvesting personnel other than members of the clan were under the authority of an heen sati (stream trustee) designated by the clan leader. Those persons, typically male, would authorize and delegate responsibility for the construction, maintenance and repair of intertidal fish weirs and traps. They would also monitor the stream or streams under their authority to assure that salmon could ascend and reach their spawning beds. Crews would be sent out in the late spring and make necessary repairs and engage in stream clean up. The heen sati would make the decision to begin harvesting once he had determined that a sufficient number of salmon had entered the stream and were on the way to their spawning grounds (Langdon 2006b, Ramos and Mason 2005).

Observers kept close track of salmon movement inshore and as the fish approached the stream mouth, they often jumped out of the water. The members of the house or clan who owned the stream, who harvested the salmon and who were the trustees empowered to insure that salmon would return would arrive at the site and celebrate the salmon return (Langdon 2007). In addition, they would sing songs of welcome and thanks, inviting the salmon to enter into their “forts” (the basket traps found associated with certain sites) (Langdon 2007). On the “forts”, there were often located carved stakes that would stick up above the water so when the returning salmon were jumping the carvings could be seen (Langdon 2007). The trap stakes were carved into the form of the crest of the clan owners of the trap (for example grizzly bear) and their purpose was so that salmon could recognize they were “giving themselves” to those who had assured their reproduction during their previous visit. One extraordinary trap stake was carved to represent the mythic Salmon Boy figure who in the Tlingit oral tradition traveled to the land of the salmon where he was taught how salmon were to be treated and brought the information back and shared it with the people (Langdon 2007) (see Fig. 9a and b).

Carved wooden trap stake depicting Salmon Boy placed on fish trap so that jumping salmon could see it on arrival at the stream - Photo by Steve Langdon

Current Status

None of the intertidal fish traps are currently in use to provide food for anyone in southeast Alaska. No restoration is being contemplated that I am aware of. People changed to the use of drag seines and purse seines for the most part around 1900 (Langdon 1977). Most of the intertidal fish traps in estuaries were outlawed by 1900 (Langdon 1990). From the 1910s to 1980s, salmon were mostly acquired from commercial seine boats captained by local Tlingit distributing fish to people. Alternately, small drag seines were taken to sites when commercial seasons were not open. The focus has been overwhelmingly on sockeye or red salmon which are found in relatively few streams. There are no real incentives to using the traps now. There are no threats to the use of intertidal fish traps as there are no current uses.

References

Ackerman, R., and R. Shaw. 1979. Beach front boulder alignments in Southeastern. Page Road et al. (eds.) Megaliths to medicine wheels: boulder structures in archeology. University of Calgary, Calgary.

Carlson, R., and J. Baichtal. 2015. A predictive model for locating early holocene archaeological sites based on raised shell-bearing strata in Southeast Alaska, USA. Geoarchaeology: An International Journal Volume 30:120–138.

Emmons, G. 1991. The Tlingit Indians, edited with additions by Frederica de Laguna. University of Washington Press, Seattle.

Laguna, F. de. 1960. The story of a Tlingit community: a problem in the relationship between archeological, ethnological, and historical methods. United States Government Printing Office, Washington.

Langdon, S. 1979. The development of salmon fishing technologies in the Prince of Wales Archipelago. Pages 287–345 M. Kennedy (ed.) The Sea in Alaska’s Past. Office of History and Archeology, Anchorage.

Langdon, S. 1987. Traditional Tlingit fishing structures in the Prince of Wales Archipelago. Pages 66–89 Fisheries in Alaska’s past: a Symposium. Office of History and Archaeology, Anchorage.

Langdon, S. 2006a. Tidal pulse fishing: selective traditional Tlingit salmon fishing techniques on the west coast of the Prince of Wales Archipelago, southeast Alaska. Pages 21–46 C. Menzies (ed.) Traditional Ecological Knowledge and Natural Resource Management. University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, Neb.

Langdon, S. 2007. Sustaining a relationship: inquiry into the emergence of a logic of engagement with salmon among the southern Tlingits. Pages 233–273 Native Americans and the Environment: Perspectives on the Ecological Indian. University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, Neb.

Langdon, S. 2019. Spiritual relations, moral obligations and existential continuity: the structure and transmission of Tlingit principles and practices of sustainable wisdom. Pages 153–182 Narvaez, D. Jacobs, E. Halton, B. Collier, and G. Enderle (eds.) Indigenous Sustainable Wisdom: First-Nation Know-How for Global Flourishing. Peter Lang, New York.

Langdon, S. 2020. Tlingit engagement with salmon: the philosophy and practice of relational sustainability. Pages 169–185 Thornton and S. Bhagawat (eds.) Routledge Handbook of Indigenous Environmental Knowledge. Routledge, New York.

Langdon, S. J. 2006b. Traditional knowledge and harvesting of salmon by HUNA and HINYAA LINGIT. FIS Final Report 02-104. Anchorage: US Department of Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service, Office of Subsistence Management, Anchorage, AK.

Langdon, S., D. Reger, and C. Wooley. 1986. Using aerial photographs to locate intertidal fishing structures in the Prince of Wales Archipelago, Southeast Alaska. Public Data File Document No. 86-9. Anchorage: Alaska Dept. of Natural Resources, Division of Geological and Geophysical Surveys, Anchorage, AK.

Moss, M., J. Hays, P. Bowers, and D. Reger. 2016. The archeology of Coffman Cove: 5500 years of settlement in the heart of Southeast Alaska. University of Oregon Museum of Natural History and the Department of Anthropology, Eugene.

Newton, R., and M. Moss. 1984. The subsistence lifeway of the Tlingit people – Excerpts of Oral Interviews. Juneau: US Forest Service, Alaska Region.

Pulu, T. 1983. The transcribed tapes of Christine Edenso. Anchorage, Ak: University of Alaska, Materials Development Center.

Ramos, J., and R. Mason. 2004. Traditional ecological knowledge of Tlingit people concerning the sockeye salmon fishery of the dry Bay Area. US Fish and Wildlife Service, Anchorage.

Smith, J. 2011. An update of intertidal fishing structures in Southeast Alaska.Alaska Journal of Anthropology 9:1–26.