Haíłzaqv (Heiltsuk) Fish Weirs and Traps

By Dana Lepofsky, Daniella LoScerbo, Heather Earle

Ancestral Connections & Geographic Extent Temporal Extent Biophysical Manipulations Target Species Ceremony & Stewardship Current Status

Large fish trap in Huyat, in the traditional territory of Heiltsuk First Nation. Note that the wall has been covered with silt and is actually 7 - 8 meters wide - Photo by Mark Wunsch

Ancestral Connections & Geographic Extent

The ancestral Haíłzaqv (Heiltsuk) built and managed fish weirs and traps throughout their territory. Oral traditions speak of the deep time connection of Haíłzaqv first ancestors to fish and fish traps (Carpenter et al. 2000, Boas 1932/1973; White 2011). This profound connection is evident in the 100’s of stone fish traps and other marine management features that have been recorded in the 22,000 square kilometers of Haíłzaqv territory (Carpenter et al. 2000; White 2006).

Temporal Extent

Several First Generation stories of the Haíłzaqv speak to the deep ancestral connections among the Haíłzaqv and fish traps (Carpenter et al. 2000; White 2006; Heiltsuk First Nation 2022). While there are no in-depth archaeological investigations of Haíłzaqv fish traps and weirs, a recent excavation of a stone alignment in Húy̓at (northern Hunter Island) provides some insights. The excavation of the outer (and thus youngest part) of the wall demonstrated that this portion of the trap was built and used over a 100- year period from 270 – 370 years ago (Heiltsuk First Nation 2022). However, the age of the nearby settlements (established ~6000 years ago), and the detailed discussion of the First Generation connections to the fish traps in Húy̓at, specifically (Boas 1932/1973), indicate its much greater time depth. Undoubtedly, systematic investigation of the many traps and weirs in Haíłzaqv territory will produce ages on par with the oldest fish traps in the broader Northwest Coast region (i.e., ~5,500 BP; see Fish Traps of the Northwest Coast).

Biophysical Manipulations

Haíłzaqv traps and weirs are located in the upper intertidal associated with streams and rivers where fish congregate. In general, there are two main forms: those constructed of wood and located in lower streams (gvúláyu) and those constructed with stone (ckvá) (Atlas et al., 2020). The rock formations vary in size and form (Pomeroy 1976). Some of the more impressive are composite features composed of a series of semi-circular traps similar in form to other features on the coast. Bowed single wall features that follow the shore are also common (photo above), as are simple rock alignments in small streams used to funnel fish further upstream (Heiltsuk First Nation 2022). In the early to mid 20th century, only smaller, semi-circular traps and holding ponds constructed closer to the fishing camps were used.

Local knowledge as well as an archaeological excavation of the large stone trap in Húy̓at demonstrate the magnitude and complexity of these engineered features as well as the changes they have undergone in recent years. In fact, according to Cyril Carpenter, many of the rock wall features that are visible today are likely remnants of the foundations used to support tall wooden lattice fences woven together with cedar bark. In fact, archaeological excavations indicate that what we see today are only the very tips of large rock foundations that we expanded and rebuilt over time (see series of three photos below). In recent years, siltation associated with logging and the cessation of on-going maintenance by the Haíłzaqv, the majority of the rock walls have been buried (Heiltsuk First Nation 2022). Elders visiting the rock walls in recent years remark on how much the walls have silted in since their childhood (White 2011).

The three photos above are of Darcy Mathews excavating the large fish trap in Húy̓at, in Haíłzaqv traditional territory. The stakes recovered under the rocks were the foundation for a wooden fence that may have supported a wooden lattice. Note cut marks on the stakes. Based on two wood samples submitted to the radiocarbon lab, this massive stone and wood fish trap was in use for at least 100 years from 270 to 370 years ago (i.e., AD 1680 - 1580). Given its enormous size, its prominent position in the Húy̓at intertidal, and that the large settlements in the bay date to many millennia ago, we expect that additional excavations would demonstrate that the trap was in use and continually refurbished for many generations.

Haíłzaqv traps and weirs were designed to allow carefully controlled harvests of fish. In the 20th century, traps were used from late summer until late fall when salmon were migrating back to their natal streams (White 2006). The fish would swim into the rock walls or be funneled into the streams with the in-coming tide and then left trapped by a closure (a gate) or by the high walls on the receding tide. The traps were designed to retain water so they could also be used as holding ponds while they were being processed. When enough fish were harvested from the trap, an opening was created either by removing rocks from the wall (White 2011) or by opening the gate in the wooden fence (Cyril Carpenter). Letting the excess fish go is part of a time-honoured conservation tradition that permeates Haíłzaqv stewardship practices (White 2006).

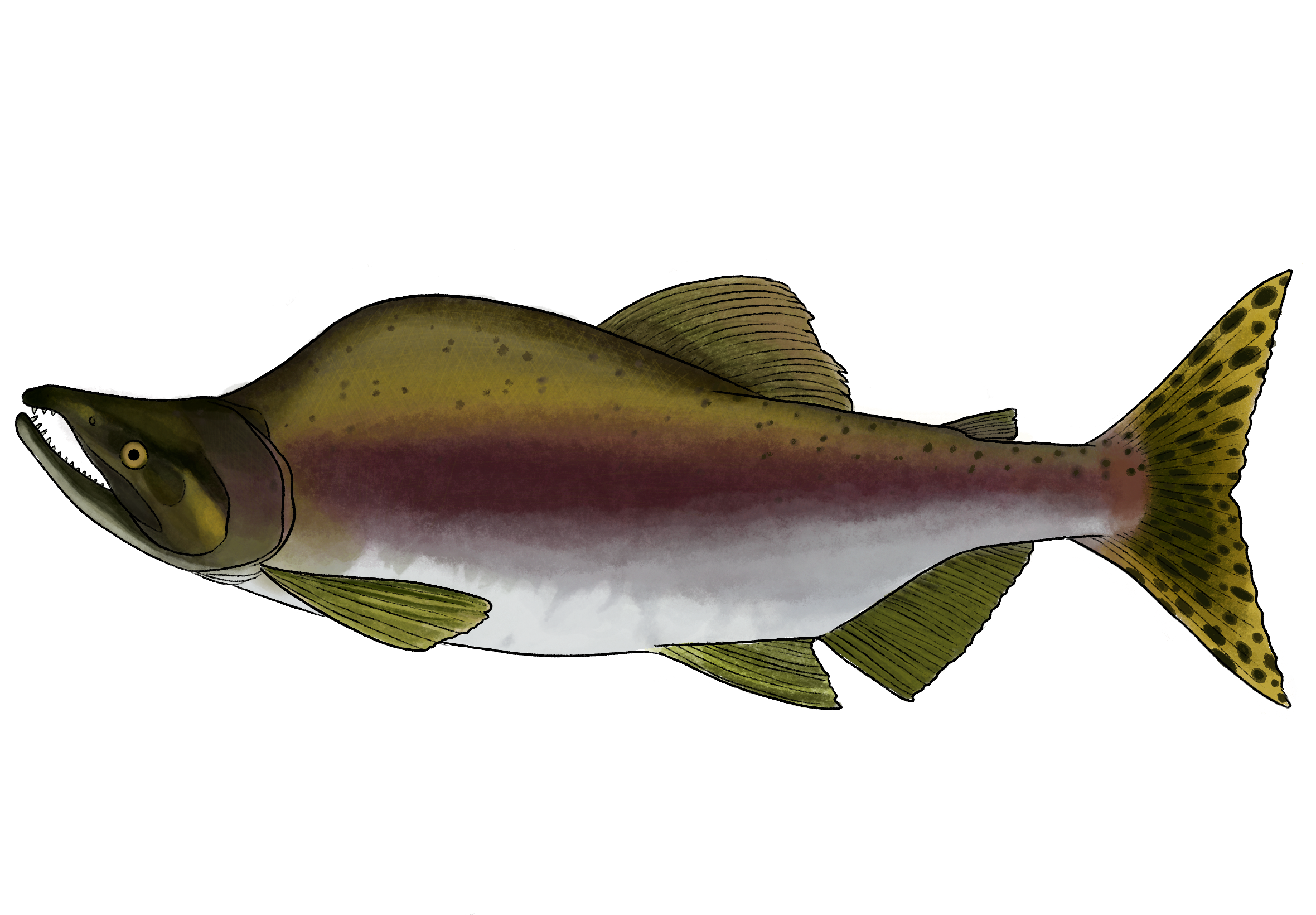

Target Species

In the 20th century fish camps, the Haíłzaqv focused their fish harvests on Pacific salmon, although herring-specific traps were also known by community members (White 2011). Four species of salmon in particular were targeted: chum (Oncorhynchus keta), pink (O. gorbuscha), coho (O. kisutch) and sockeye (O. nerka). The same trap could be used throughout the summer and fall to target the different runs of salmon (White 2011). The Haíłzaqv targeted pink and chum salmon in more advanced states of maturation as these had lower fat content making them ideal for drying and storing. Sockeye and coho were often eaten fresh.

In recent years Haíłzaqv targeted pink and chum salmon in more advanced states of maturation as these had lower fat content making them ideal for drying and storing (White 2006); sockeye and coho were often eaten fresh (White 2006; Atlas et al., 2020). Many older Haíłzaqv community members remember helping harvest and smoke thousands of fish in smokehouses . Women played a major role in all aspects of the harvesting, smoking, and fish selection (White 2006; Atlas et al., 2020; Heiltsuk First Nation 2022).

Ceremony & Stewardship

In addition to constructing fish traps and weirs, the Haíłzaqv employed a range of stewardship practices that help keep fish stocks healthy. In particular, these include creating river pools and removing river debris to facilitate the upstream migration of salmon (Jones 2002; Heiltsuk First Nation 2022). Furthermore, often the weak or small salmon were chosen for food, and males or females were selected depending on how the fish would be processed. Equally important to the health of the fish stocks are the Haíłzaqv prayers, songs, and the respect given to all non-human beings and their homes.

Among the Haíłzaqv their relationships with fish were nested within gvil’as –belief systems and protocols about the right way to behave with the other human and non-human beings). Haíłzaqv principles of stewardship emphasize the responsibility that comes with resource rights as well as a focus on what is left behind, rather than what is taken (Housty et al., 2014; Atlas et al., 2020). This responsibility was enacted in the tending of natal streams, sex selection and selecting weaker individuals, and in the opening of the traps after the harvest was finished to allow the remaining fish to return to the ocean to spawn Atlas et al., 2020).

The management of fish and fish traps and weirs was also regulated by the Haíłzaqv system of ownership and tenure. In recent years, traps belonged to different families who were responsible for their construction (Heiltsuk First Nation 2022). However, the association of traps with chiefs and hereditary prerogatives in several of the First Generation stories (Carpenter et al. 2000), reflects how completely fish and fishing are intertwined in Haíłzaqv social networks.

Like many Northwest Coast peoples, the Haíłzaqv perform a First Fish ceremony for the first large salmon returning to a community, with offerings of down and red cedar bark to thank the fish for returning to feed them (Drucker 1950:222; Lepofsky and Caldwell 2013). Following this ceremony, a temporary moratorium was implemented, allowing the first runs to reach their spawning grounds (Atlas et al., 2020). These practices and ceremonies exemplify the connections between human and salmon, and the nurturing of what people saw as a reciprocal relationship with their non-human kin, reflecting the belief that salmon willingly offered themselves as sustenance (Cullon 2017; Lepofsky and Caldwell 2013; Atlas et al., 2020).

Coming together for these ceremonies also allowed for the strengthening of social relationships and cultural knowledge through communal harvesting, feasting, trading, and other rituals. Positioning salmon, and other resources, within the larger social framework of Northwest Coast peoples would have helped ensure the continuation of proper tending, management, ownership, and control for generations to come (Lepofsky and Caldwell 2013).

Small riverine fish trap in Huyat. In the early to mid 1900's, such smaller features were used and maintained by smaller family groups - Photo by Mark Wunsch

Small riverine fish trap in Huyat, view from above - Photo by Mark Wunsch

Current Status

Fish traps in Haíłzaqv territory, and across the Northwest Coast, are largely not used today, although thousands of these structures can still be seen on the landscape and are testament to the powerful and enduring relationship between Indigenous People and fish. There are key factors that have contributed to the disuse of this practice.

In the mid-nineteenth century, Indigenous salmon management was disrupted and replaced by colonial structures and authorities (Atlas et al., 2020). This was done through various mechanisms including the outlawing of fish traps in the late 1800s. In the early 1900’s, Department of Fisheries and Oceans actively destroyed fish traps in Haíłzaqv territory because there was a belief that they were damaging stocks – despite the fact that the fisheries had been successfully managed by the Haíłzaqv for countless generations. Over time, coastal First Nations were excluded from fisheries resources and decision making with increasingly centralized systems of resource management control. The management policies that followed led to declining returns, inhibiting Indigenous people from harvesting salmon for subsistence. Extensive and aggressive resource extraction in the Pacific Northwest, such as logging, mining, and dam construction, has further contributed to declines with widespread salmon habitat destruction (Atlas et al., 2020). This transformation away from long-standing, place-based management, has dramatically altered the methods, scales, and locations of Indigenous fish harvesting and coastal First Nations continue to fight for access and governance authority today (Atlas et al., 2020).

Although legal cases have resulted in monetary compensation for some of these losses, the root causes of the situation, the imbalance of power in decision making authority and massive declines in salmon abundance, are rarely addressed (Atlas et al., 2020). Nonetheless, Haíłzaqv people are reviving some of these ancestral practices. A traditional-style weir has been restored in the Koeye River, within Haíłzaqv territory. This weir is contributing not only to salmon population monitoring and sockeye harvest, but also to a revival of weir building among Haíłzaqv people (Atlas et al., 2020).

More Information:

Videos, pictures and descriptions: https://www.hauyat.ca/living/tending-and-harvesting-2/traps-and-gardens-2/fish-traps.html

Heiltsuk Stone Fish Traps video by The Tyee: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jQlQO11cT-8&ab_channel=TheTyee

References

Atlas, W. I., N. C. Ban, J. W. Moore, A. M. Tuohy, S. Greening, A. J. Reid, N. Morven, E. White, W. G. Housty, J. A. Housty, C. N. Service, L. Greba, S. Harrison, C. Sharpe, K. I. R. Butts, W. M. Shepert, E. Sweeney-Bergen, D. Macintyre, M. R. Sloat, and K. Connors. 2021. Indigenous systems of management for culturally and ecologically resilient pacific salmon (Oncorhynchus spp.) fisheries. BioScience 71:186–204.

Boas, Franz. 1932. Bella Bella tales. Memoirs of the American folk-lore society, Vol. XXV. Reprinted 1973 by Kraus Reprint Co., Millwood, New York.

Carpenter J, Humchitt C, Eldridge M. 2000. Final report, Fisheries Renewal BC Research Reward, Science Council of BC, reference number FS99-32, Heiltsuk Cultural Education Centre, July 2000. Unpublished manuscript on file at the Heiltsuk Cultural Education Centre. Bella Bella, BC.

Cullon, D.S. 2017. Dancing salmon: human-fish relationships on the Northwest Coast. PhD dissertation, Dept. of Anthropology, University of Victoria, BC.

Gauvreau, A. M., D. Lepofsky, M. Rutherford, and M. Reid. 2017. “Everything revolves around the herring” the Heiltsuk–herring relationship through time. Ecology and Society 22: art10.

Heiltsuk First Nation. 2022. Húy̓at Fish Traps web page. http://www.hauyat.ca/living/tending-and-harvesting-2/traps-and-gardens-2/fish-traps.html, Accessed 25 January 2022.

Housty, W. G., A. Noson, G. W. Scoville, J. Boulanger, R. M. Jeo, C. T. Darimont, and C. E. Filardi. 2014. Grizzly bear monitoring by the Heiltsuk people as a crucible for First Nation conservation practice. Ecology and Society 19:art70.

Jones, J.T., 2002. “We looked after all the salmon streams”: traditional Heiltsuk cultural stewardship of salmon and salmon streams: a preliminary assessment, Environmental Studies M.A. thesis, University of Victoria, Victoria, BC.

Lepofsky, D., and M. Caldwell. 2013. Indigenous marine resource management on the Northwest Coast of North America. Ecological Processes 2:12.

Pomeroy, J. A. 1976. Stone fish traps of the Bella Bella region. Current Research Reports, Pages 165–173, Roy L. Carlson (ed), Department of Archaeology, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, BC.

Pomeroy, J. A. 1980. Bella Bella settlement and subsistence. PhD dissertation, Department of Archaeology, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, BC.

White, E. 2006. Heiltsuk stone fish traps: products of my ancestors’ labour. MA Thesis, Department of Archaeology, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, BC.

White, Elroy. 2011. Heiltsuk stone fish traps on the Central Coast of British Columbia. Pages 75-90 M.L. Moss, and A. Cannon (eds.) The archaeology of North Pacific fisheries. University of Alaska Press, Fairbanks.