Loko I’a - Hawaiian Fish Ponds

By Brenda Asuncion and Amanda Millin

Ancestral Connections & Geographic Extent Temporal Extent Biophysical Manipulations Target Species Ceremony & Stewardship Current Status

Kahina Pōhaku in Moanui, Molokaʻi - Photo by Scott Kanda

Ancestral Connections and Geographic Extent

Loko iʻa were made and managed by the Indigenous people of the Hawaiian archipelago. The first loko iʻa is thought to have been built by Kūʻula, as described in the following moʻolelo (story; literally succession of speech):

Creation: Kū‘ula-kai had a human body, but was possessed with mana kupua (supernatural powers), in directing and controlling the fish of the sea. While Ku‘ula and his wife (Hina-puku-iʻa, goddess of fishermen) were living at Leho‘ula on the island of Maui, he devoted all his time to his chosen vocation of fishing. His first work was to construct a loko iʻa (fishpond) handy to his house, but near the shore where the surf breaks, and he stocked this pond with all kinds of fish. Upon a rocky platform, he also built a house, which he called by his own name, Kū‘ula, to be sacred for the fishing kapu (laws and regulations; literally ‘forbidden’). Here he offered the first fish caught to the fish god, and because of his observances, fish were laka loa (obedient) to him. All he had to do was to say the word, and fish would appear.

Some scientists suggest this moʻolelo of the first loko iʻa is more than folklore. Kūʻula could have been a real person who used empirical observation and repetitive field experience to develop a deep understanding of oceanography and coastal ecology, including water chemistry, fish behavior, and tidal flows (McDaniel 2018).

Loko iʻa currently exist as both private and public resources in Hawaiʻi, with “ownership” held by both private landowners (e.g., families, estates, commercial properties) as well as various departments within the State of Hawaiʻi and the federal government of the United States of America. Importantly, most lands seaward of the high tide mark are considered public resources in Hawaiʻi, however, loko iʻa are the only shoreline and submerged properties that can be privately owned.

Researchers estimate that prior to James Cook’s arrival in 1778, there were 488 loko iʻa throughout ka paeʻāina o Hawaiʻi (the Hawaiian archipelago) reliably producing about 300 pounds of herbivorous fish per acre per year (Chang et al. 2019 and Costa-Pierce 1987) (DHM, 1990). By 1901, only 99 of them were commercially active, producing 680,000 pounds of fish per year, including 485,000 pounds of ʻamaʻama (striped mullet; Mugil cephalus) and 194,000 pounds of ʻawa (milkfish; Chanos chanos) (Cobb 1901).

Today, most of the 488 loko iʻa sites are degraded. For the sites that are partially intact, there are communities and stewardship groups who are actively restoring or have expressed interest in reviving the integrity and productivity of these places. Hui Mālama Loko Iʻa, facilitated by the local grassroots nonprofit KuaʻĀina UluʻAuamo, (KUA) is a growing network of these fishpond practitioners and organizations. The network currently includes over 40 fishponds and complexes across the Hawaiian islands, with over 100 fishpond owners, workers, supporters, and stakeholders.

Huilua in Kahana, O’ahu - Photo by John Johnson

Fishpond wall at Waiaʻōpae, Lānaʻi - Photo by Scott Kanda

Temporal Extent

Some specific loko iʻa have been radiocarbon dated with their ages varying. Evidence suggests that Hawaiian loko iʻa are between 1,500 and 1,800 years old (Costa-Pierce 1987).

Biophysical Manipulations

Hawaiian loko iʻa span the normal salinity range of water and comprise a continuum from agriculture to aquaculture to create an integrated farming system.

Loko iʻa kalo are upland loʻi kalo (taro patches) modified to include freshwater aquaculture. Loʻi themselves are agricultural innovations that fundamentally rely on environmental modifications to use stream and/or spring water and importantly, return water to its hydrological system to eventually flow to the ocean.

Loko wai are artificial and natural freshwater lakes excavated for or modified for aquaculture, respectively.

Loko puʻuone have a puʻuone (sandbar) separating them from the sea, and an auwai kai (irrigation channel) connects them, allowing sea level inputs to rise and fall with the tide and for fish to self recruit into the ponds. These also have freshwater inputs from springs, streams, submarine groundwater, or adjacent aquifers.

Loko kuapā are built along the shoreline, usually on top of a reef flat with volcanic rock and/or coral to build its semi-circular kuapā (rockwall). They contain all the marine biota of the original reef environment.

Loko ʻumeʻiki are fish traps (similar to fish traps found in Oceania) rather than a pond. Although similar to loko kuapā, ʻumeʻiki (literally meaning to pull tight) have semi-circular walls that were partially or wholly submerged at high tide to give the fish entry. Low tide prevents escape.

Loko Kaheka and Hapunapuna are natural pools for holding fish but are not set up as self-sustaining ecosystems.

Loko puʻuone, kuapā, and ʻumeʻiki all utilize a system of sluice gates call mākāhā. (Costa-Pierce 1987 and DHM, 1990)

Different types of Loko I’a - Figure modified from Apple and Kikuchi 1975 by Costa-Pierce 1987

Target Species

Loko iʻa were designed to predominant targeted herbivorous fish amaʻama (striped mullet; Mugil cephalus), awa (milkfish; Chanos chanos), moi (Pacific threadfin; Polydactylus sexfilis), and ʻāholehole (Hawaiian flagtail; Kuhlia sandvicensis). Loko iʻa kalo farmed taro (Colocasia esculenta) alongside fish (Costa-Pierce 1987).

A more thorough list of target and non-target species for each type of pond can be seen in the figure below.

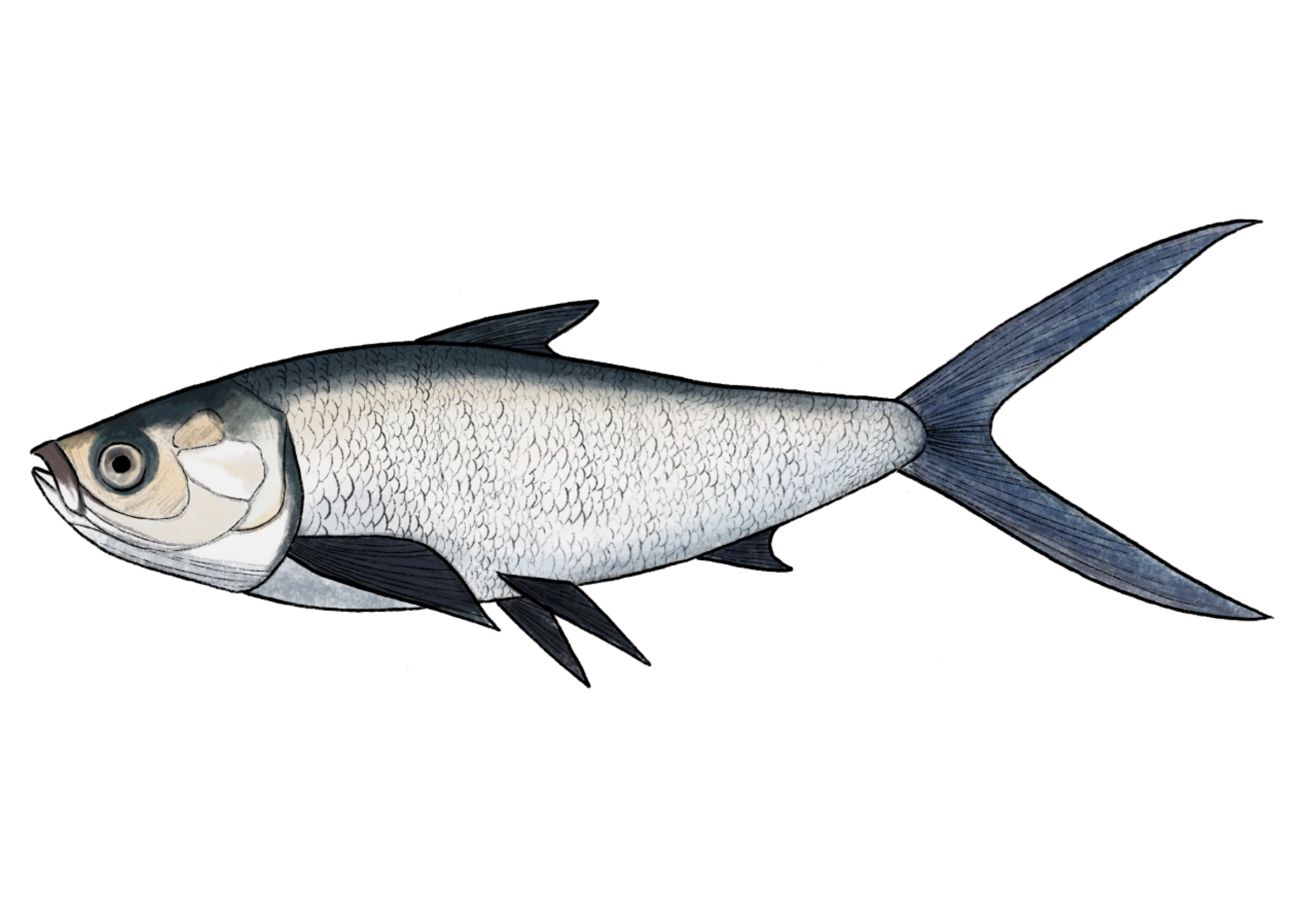

Awa, milkfish (Chanos chanos) - Illustrated by Lilly Crosby

‘ama’ama, striped mullet (Mugil Cephalus) - Illustrated by Lilly Crosby

Species caught in different types of Loko I’a - Figure modified from Kikuchi 1976.

Ceremony & Stewardship

Much of the stewardship practice and protocol of loko iʻa uphold a relationship of reciprocity between humans and the natural environment. Both kilo (the practice of observing, looking closely, and examining the surrounding environment) and adaptive management frameworks such as kaulana mahina (the Hawaiian lunar calendar) inform restoration work as well as harvest. Also, Kūʻula fishing shrines exist not only at loko iʻa but at fishing sites throughout Hawaiʻi and their function is to receive offerings and intentions for abundant catches.

Management: Loko iʻa were used to provide a reliable, convenient, and ever-ready supply of fresh seafood for the ruling aliʻi (chief) and the royal court. Larger ponds belonged to royalty and were a symbol of status and economic wealth. Smaller loko iʻa might have belonged to commoners. However, royalty appointed specific managers to oversee daily operations (Keala et al. 2007). These managers included: konohiki (similar to a superintendent), kiaʻi loko (a highly respected position that was passed down generationally through families), and haku-ʻohana (the most senior of the land tenants, who spoke for the ʻohana in meetings with konohiki) (Keala et al. 2007, Kikuchi 1973 and Apple and Kikuchi 1975).

Current Status

The role of kiaʻi loko has evolved as the contexts of land tenure, employment, and other socioeconomic aspects have changed in Hawaiʻi. Many fishpond practitioners today work as volunteers outside of their primary sources of employment. There are rare cases of genealogical connections and it is anticipated that more of these familial relationships to loko iʻa will be re-discovered as the community of practices grows.

Some community groups have evolved to form non-profit organizations to employ staff in fishpond restoration and management. In 2004 some of these organizations came together to form the Hui Mālama Loko Iʻa (group that cares for fishponds). Their intent was to collaborate and share challenges, successes, and resources. As the Hui has grown over the years, they have articulated hopes that future generations can create sustainable livelihoods as kiaʻi loko.

Currently, the barriers that challenge this vision include a lack of access to loko iʻa that are owned but not actively managed by the State of Hawaiʻi, drastically reduced wild populations of target species to stock loko iʻa, and the compromised ecological conditions at loko iʻa that have been neglected for decades and are often overrun with invasive species (both terrestrial and marine) and filled in with sediment.

Hui Mālama Loko Iʻa Gathering 2019

More Information

Hui Mālama Loko Iʻa: http://kuahawaii.org/huimalamalokoia/

References

Apple, R. A., and W. K. Kikuchi. 1975. Ancient Hawaii shore zone fishponds: an evaluation of survivors for historical preservation. National Park Service, Honolulu.

Chang, K. K. J., C. K. H. Young, B. F. Asuncion, W. K. Ito, K. B. Winter, and W. C. Tanaka. 2019. KuaʻĀina Ulu ʻAuamo: grassroots growing through shared responsibility. University of Oklahoma Press, Publishing Division of the University.

Cobb, J. N. 1905. The commercial fisheries of the Hawaiian Islands. U. S. Govt. Print. Off., Washington.

Costa-Pierce, B. A. 1987. Aquaculture in ancient Hawaii. BioScience 37:320–331.

Moon, O’Connor, Tam, and Yuen. 1990. Hawaiian fishpond study : islands of Hawaii, Maui, Lanai and Kauai. DHM Inc., Honolulu.

Keala, G., J. Hollyer, and L. Castro. 2007. Loko I’A - A manual on Hawaiian fishpond restoration and management. College of Tropical Agriculture and Human Resources, University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa.

Kikuchi, W. K. 1973. Hawaiian aquacultural system. Ph.D. Dissertation, Department of Anthropology, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ.

Kikuchi, W. K. 1976. Prehistoric Hawaiian fishponds. Science 193:295–299.

McDaniel, J. 2018. The Return of Kuʻula: restoration of Hawaiian fishponds. Hawai’i Sea Grant 1:4–11.