Estuarine root gardens of the northwest coast

By Meredith Fraser, Melissa Poe, Dana Lepofsky, and Isabelle Maurice-Hammond

Ancestral Connections & Geographic Extent Temporal Extent Biophysical Manipulations Target Species Ceremony & Stewardship Current Status

Songhees root garden at Tl'ches - Photo by Isabelle Maurice-Hammond

Ancestral Connections & Geographic Extent

Evidence of this resource stewardship practice has been documented in ethnographic accounts of Indigenous Peoples throughout the Northwest Coast of North America including the Quileute, Quinault, Makah, Coast Salish, Kwakwaka’wakw, Nuu-chah-nulth, Nuxalk, Heiltsuk, Haida, Tsimshian, and Tlingit Peoples (Gunther 1945; Deur 2005; Turner, Deur & Lepofsky 2013). The current holders of land jurisdiction and usufruct rights differ by location, see below for cases of where, and by whom, root gardening is currently being practiced.

There is evidence of this practice along the west coast of North America from Alaska through British Columbia and extending as far south as Oregon (Deur 2005). However, there are some regions in which root gardens have not been documented (e.g.; Northern Coast Salish territory). Whether this reflects a real absence in the practice or a gap in our knowledge, is not known. Estuarine root gardening has likely fluctuated through time and space depending on a range of social-ecological factors including the productivity of the land, the relative importance of starchy foods in Indigneous diet, and in recent history, shifting access to traditional territories as a result of colonization.

Temporal Extent

Indigenous knowledge holders tell us that estuarine root gardens have been tended and stewarded for millennia (Deur 2005). This is also reflected in language including ancient and etymologically distinct terms associated with tending practices and types of garden management, units of property tenure, and place names describing soil created within the gardens which suggest long histories (Deur 2005). Moreover, their antiquity is further suggested by the fact that they are part of a continuum of foreshore management ecosystems – some of which have been definitively dated to at least 3500 years ago (clam gardens; Smith et al. 2019)

Attempts to radiocarbon date buried soils or charcoal associated with root gardens have so far been limited and have resulted in only recent dates. The difficulty of determining the age of these practices is illustrated in attempts to date a dense clover patch on the island archipelago of Tl’chés, Lekwungen territories. Here, a piece of below-ground charcoal was dated to about 500 years ago. However, it is impossible to know whether this charcoal originates from cultivation practices associated with clover, or from some other cultural activity. Finding datable material associated with root garden initiation is hampered in sites where tidal action continuously deposits and removes older sediments and by determining if the datable material is associated directly with terrace construction and use. For instance, recently a piece of charcoal associated with fire cracked rocks extracted from the base of a root garden rock wall in Ahousaht territory yielded a date of approximately 1000 years old. In this case, all we can say for certain is that this date pre-dates the building of the rock wall by some unknown amount of time and that the garden is younger than this date. (Stafford 2020). The removal of datable materials from the base of rock walls is a promising avenue for further research and is currently being deployed on the remnant rock wall features of the Nimpkish River garden site on ‘Namgis First Nation territory (Maurice-Hammond, ongoing). This technique has proven successful in determining initiation dates of age of clam gardens on the Northwest Coast (Smith et al. 2019).

Long term cultural and bio-physical pressures at these sites and their effects on site morphology present another challenge to our understanding of the spatial and temporal distribution of coastal root gardens. At the Nimpkish River root garden, for example (a site well documented by Boas [1934] and Deur [2000]), the cessation of management practices has led to the collapse of many rock wall structures.. Sites that no longer, or perhaps never had stone walls, are ever more difficult to identify, though work is currently underway to determine whether soil chemistry might be deployed in tracing evidence of past management practices (Maurice-Hammond, ongoing). Attempts to date the practice in areas that lack physical structures is an especially salient issue in places where communities no longer retain the knowledge about specific coastal root garden management practices or locations, as is the case in Lekwungen/Songhees territory.

Songhees root garden at Tl'ches - Photo by Darcy Mathews

Biophysical Manipulations

Estuarine root gardens exist where the land meets the sea, as part of a continuum of ecosystems and stewardship practices along the coast (Mathews & Turner 2017). Since the form of root gardens, like many traditional management features, are designed to take advantage of natural geomorphic and ecological processes, they can vary in their specific landscape modifications. Such modifications range in intensity and structural design, depending on the location.

Physical and ecological modifications of estuarine root gardens were diverse. Along sloped banks, people created terraces parallel to the shoreline by building low rock or wood retaining walls. This reduced the foreshore slope and expanded and made more accessible the tidal zone in which these root foods naturally thrive. It is possible that terraces may have also served to demarcate individually owned and managed plots. In flatter terrain, gardens were demarcated with wood (e.g., Boas 1934).

The soil in the plots themselves were managed by tilling when harvesting using a specialized digging stick, thus aerating the soil. As in most gardening practices, large rocks were also removed from the plot to facilitate growth and increase growing area. Given the gardens’ location in the upper salt marsh and tidal zone, gardens accumulated nutrient rich sediments from riverine sources in addition to marine sources, through occasional flooding during peak tides and storm events. Additional management included weeding, to remove unwanted/competitive plants, and selective harvesting and in situ replanting and transplanting of root foods.

References: (Cruze et al. 2018; Deur 2005; Turner et al. 2013; Turner & Kuhnlein 1982).

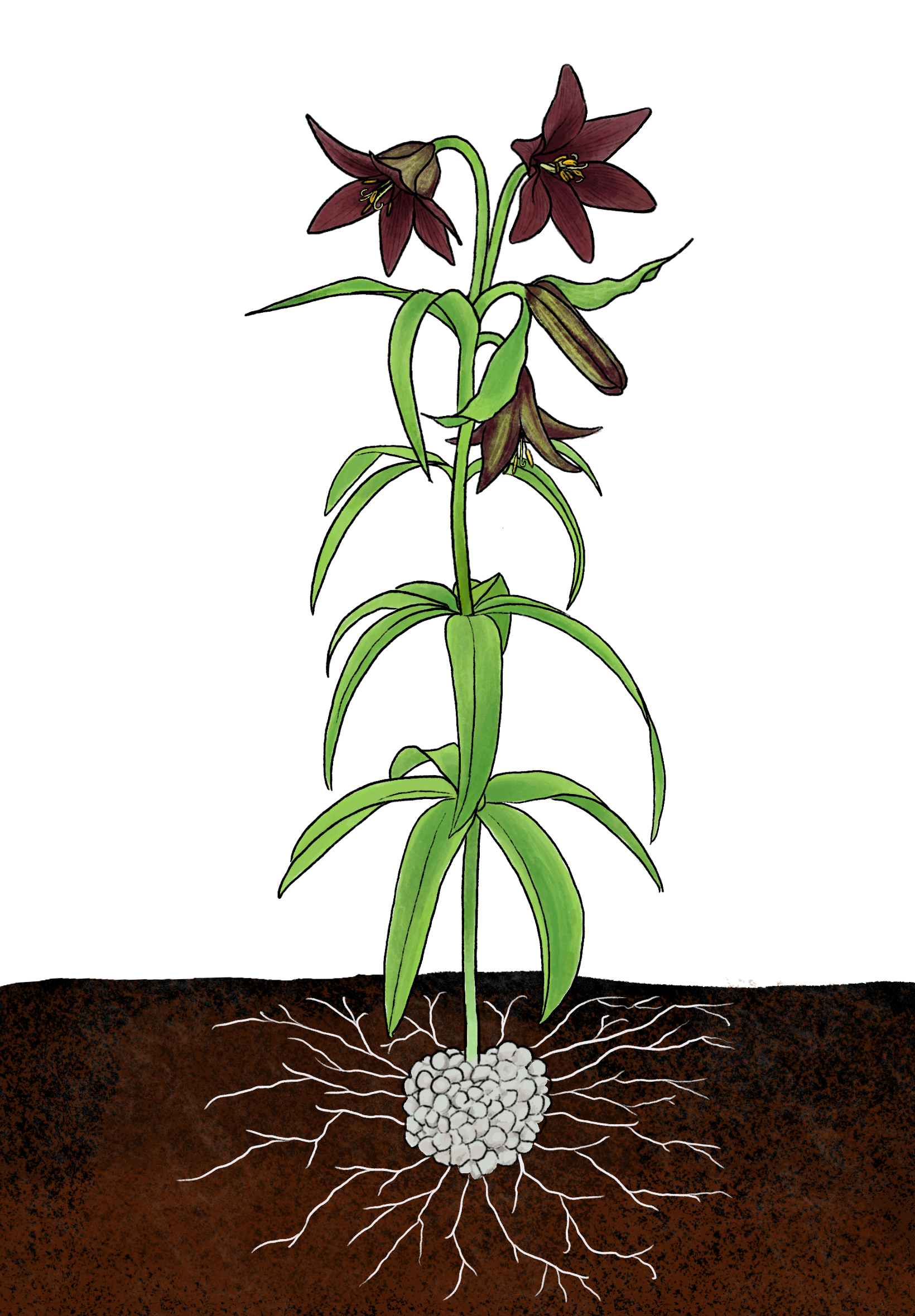

Target Species

Target species include springbank clover (Trifolium wormskioldii), Pacific silverweed (Potentilla egedii), Northern riceroot (Fritillaria camschatcensis), and Nootka lupine (Lupinus nootkatensis). In addition, secondary species such as ducks, geese and other waterfowl attracted to root garden habitat and roots for food were also harvested.

References: (Deur 2005; Edwards 1979; Turner et al. 2013; Turner & Kuhnlein 1982).

Ceremony & Stewardship

Stewardship (Pre-harvest management):

Stewardship included a wide range of practices including wall construction, terracing of estuarine areas, tending of soil, selective root harvesting, and transplanting (see above). Tending practices contributed to improving root food productivity, form and length, ease of access and cleaning, and predictability (Deur 2005; Turner and Kuhnlein 1982). The knowledge encompassed within these practices was passed down intergenerationally. Historically, individual root garden plots were owned and tended by specific families, with ownership held by successive generations through a sophisticated tenure system (Deur 2005; Boas 1934).

Ceremony (Post-harvest social-ecological context): How is the harvest prepared, shared, and distributed?

The nutritious starchy roots produced from gardens were prized foods often used as gifts in potlatch ceremonies and celebrated through ceremonial feasts 2-3 months following harvest (to allow time for the roots to grow sweet; Deur 2005). The longer roots were typically reserved for leaders and high-class people during feasts, and shorter roots kept for household and common use (Turner and Kuhnlein 1982 citing Boas 1921). Note that amongst the Kwakwaka’wakw root feasts, Chiefs would give speeches that recognized the root plots that had supplied the feast and recounted the lineages through which they inherited these plots (Deur 2005). Specific to Potentilla pacifica (Pacific silverweed), Boas (1921) writes: “this is the cinquefoil that holds a prominent place in the tales” (as cited in Gunther 1945 and Haskin 1934) indicating that these roots also carried cultural importance through stories and ceremony. Roots were also part of regional trade networks where people in places with abundant root foods traded for eulachon grease and other goods (Deur 2005).

It was primarily women who maintained root gardens and harvested and cooked the roots. Special shelters were sometimes constructed for the harvest days. In some places, pit ovens for cooking roots were shared communally and women had individual knots used to distinguish their roots bundles from other women’s (Turner and Kuhnlein 1982).

Springbank clover and Pacific silverweed are often cooked using steaming and pit roasting methods and eaten soon after or dried and stored. The roots are often eaten dipped in grease and were only occasionally eaten raw by women as they were harvested (Deur 2005; Turner and Kuhnlein 1982). Consultants described to Turner and Kuhnlein that the clover roots taste like cooked beansprouts and silverweed like sweet potato.

Harvest at the Songhees root garden at Tl'ches - Photo by Isabelle Maurice-Hammond

Current Status

There is a current focus on these ecosystems today as part of a larger movement towards cultural assertions, reconnections, and food sovereignty. There are currently efforts underway to restore and revitalize estuarine root gardens by a number of groups across the Northwest Coast of North America:

The λ’aayaʕas Project is a community-based action research project of the Nuu-chah-nulth communities of Clayoquot Sound, described by Pukonen (2008) as a way to strengthen community knowledge of root gardens and their traditional management practices, with aims to engage students, maintain cultural identity and community well-being.

Another effort at Tl'chés (Chatham Islands, British Columbia, Canada) applies Songhees' cultural practices and traditional knowledge to develop a restoration plan for a remnant root garden (Nicholas 2017; Boseman 2019).

A third example sought to replicate and measure the ecological effects of the Indigenous management protocols of tekkillakw (tilling and weeding) described by Kwaxsistalla, Clan Chief Adam Dick, of the Qawadiliqalla Clan in the Kingcome Inlet area, BC. This study and restoration project found that tekkillakw significantly increased the abundance of Pacific silverweed, albeit decreased root size. Also, bitter tannin concentrations in root species were found to be highest in the late summer and lowest in the spring and fall, consistent with the ethnographic accounts of harvest timing in fall after the first frost and spring (Lloyd 2011; Deur 2005).

Deur (2005) describes assimilation, policies, loss of language, and cultural change as impacts that have eroded the practice and knowledge of estuarine root gardens, and therefore ethnographic documentation of the practice is limited. This is also in part owing to the early ethnographers, which were predominantly men, consulting mainly with men, who were less likely to be engaging in root garden activities, a predominantly women’s responsibility (Lepofsky 2004, Turner 2020). Archaeological research on plant practices is also challenged by the material nature of plants and decomposition. With regards to the extent to which root gardening practices have continued or been lost, when we consider the presence of these roots in contemporary Northwest Coast diets, their consumption continues in the 21st century (personal communication, Melissa Poe). Deur (2005) also notes that while active root garden sites maintenance may have been abandoned, these sites remained places for hunting waterfowl.

More Information

References

Hunt, G., and F. Boas. 1921. Ethnology of the Kwakiutl. Washington Government Printing Offices, Washington, Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution.

Boas, F. 1934. Geographical names of the Kwakiutl Indians. Columbia University Press, New York.

Nicholas, G.R. Ecocultural restoration of a coastal root garden on Tl’chés(Chatham Island), B.C. MA Science Thesis, Ecological Restoration Program Faculty of Environment. Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, BC.

Cruz, O., B. Drouillard, M. Mund, and B. Pearse. 2018. Changing the climate around estuarine root garden management with the Kwakwaka’wakw. Journal of the Vancouver Island Public Interest Research Group 1:9.

Deur, D. 2000. A domesticated landscape: Native American plant cultivation on the Northwest Coast of North America. PhD dissertation, Department of Geography, Louisiana State University, Louisiana.

Deur, D., and N.J. Turner (eds.). 2005. Keeping it living: traditions of plant use and cultivation on the northwest coast of North America. University of Washington Press, Seattle.

Deur, D., N. Turner, A. Dick, and K. Recalma-Clutesi. 2013. Subsistence and resistance on the British Columbia coast: Kingcome village’s estuarine gardens as contested space. BC Studies 179: 13-37.

Günther, E. 1945. Ethnobotany of western Washington: the knowledge and use of Indigenous plants by Native Americans. University of Washington Press, Seattle.

Lepofsky, D. 2004. The Northwest. In plants and people in ancient North America, Pages 367-464 P. Minnis (ed.). Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington.

Lepofsky, D., C. G. Armstrong, S. Greening, J. Jackley, J. Carpenter, B. Guernsey, D. Mathews, and N. J. Turner. 2017. Historical ecology of cultural keystone places of the Northwest Coast. American Anthropologist 119:448–463.

Lloyd, T. 2011. Cultivating the t’əkkillakw the ethnoecology of λəksəm, Pacific silverweed or cinquefoil [Argentina egedii (Wormsk.) Rydb.; Rosaceae]: lessons from Clan Chief Adam Dick, Kwaxsistalla of the Qawadiliqəlla Clan of the Dzawada7ēnuxw of Kingcome Inlet (Kwakwaka’wakw). Master’s Thesis, School of Environmental Studies, University of Victoria., Victoria.

Mathews, D. L., and N. J. Turner. 2017. Ocean cultures: Northwest Coast ecosystems and Indigenous management systems. Pages 169—206. P. S. Levin and M. R. Poe (eds.) Conservation for the Anthropocene Ocean. Academic Press, San Diego, CA.

Nicholas, G. R. 2017. Eco-cultural restoration of wetlands at Tl’chés (Chatham Islands). MA Thesis, Ecological Restoration Program, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, BC.

Pukonen, J. C. 2008. The λ’aayaʕas project: revitalizing traditional Nuu-chah-nulth root. gardens in Ahousaht, British Columbia. Master’s Thesis, School of Environmental Studies, University of Victoria, Victoria.

Smith, N. F., D. Lepofsky, G. Toniello, K. Holmes, L. Wilson, C. M. Neudorf, and C. Roberts. 2019. 3500 years of shellfish mariculture on the northwest coast of North America. PLOS ONE, 14(2), 1-18.

Stafford, J. 2020. Archaeological impact assessment of the Anderson Creek (Ahousaht) water main upgrade and alteration to archaeological sites DHSM-58, 138, 142 and 143. Prepared for and distributed to: Ahousaht First Nation, McGill & Associates, and Archaeology Branch of BC, Victoria, BC.

Turner, N. J., D. Lepofsky, and D. Deur. 2013. Plant management systems of British Columbia’s First Peoples. BC Studies 179:107-133.

Turner, N. J., and H. Kuhnlein. 1982. Two important “root” foods of the Northwest Coast Indians: Springbank Clover (Trifolium wormskioldii) and Pacific Silverweed (Potentilla anserina ssp. pacifica). Economic Botany 36: 411–432.

Turner, N. J. 2020. From “taking” to “tending”: learning about Indigenous land and resource management on the Pacific Northwest Coast of North America. ICES Journal of Marine Science 77:2472–2482.

Other Important References on Root Gardens

Drucker, P. 1951. The Northern and Central Nootkan tribes. Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 144. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution.

Edwards, G. 1979. Indian spaghetti. The Beaver. Autumn: 4-1.

Haskin, L. L. 1934. Wild flowers of the Pacific Coast. Binfords and Mort, Portland, Ore.

Jackley, J., L. Gardner, A. F. Djunaedi, and A. K. Salomon. 2016. Ancient clam gardens, traditional management portfolios, and the resilience of coupled human-ocean systems. Ecology and Society 21:20.

Joseph, L. 2012. Finding our roots: ethnoecological restoration of lhasem (Fritillaria camschatcensis (L.) Ker-Gawl), an iconic plant food in the Squamish River Estuary, British Columbia, MA Thesis, School of Environmental Studies, University of Victoria, Victoria.

Pringle, H. 2017. In the land of lost gardens. Hakai Magazine.